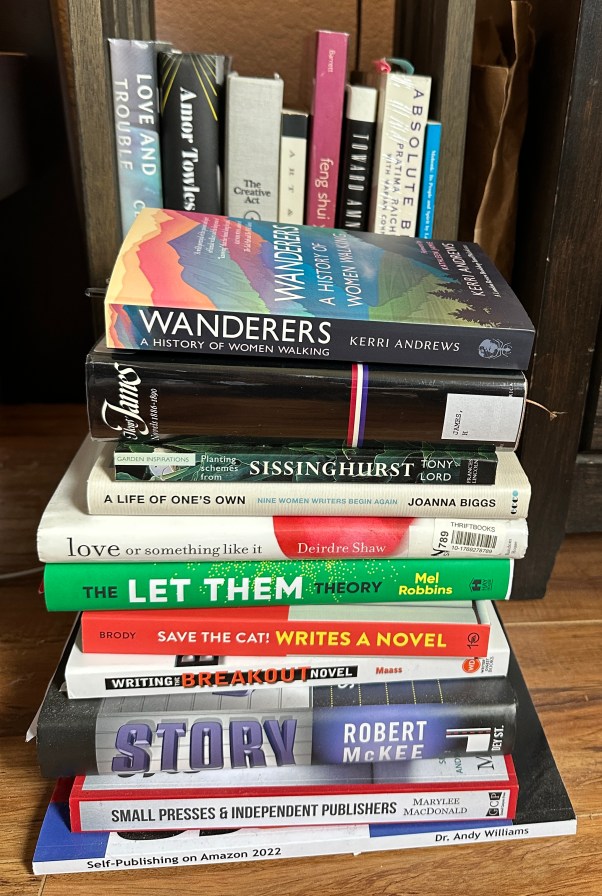

Like most, I am enriched by words. Writing them, reading them, listening to and endlessly speaking them. Words arrive as gifts, born out of my imagination or within the printed material piled up throughout our home. In Kerri Andrews’ book, Wanderers, she wrote, “On foot, Woolf walks out into the fields and into her mind.” The two activities, walking and writing, mesh for me as well. Virginia Woolf cements the idea in her May 11, 1920 diary entry, “Directly one gets to work one is like a person walking, who has seen the country stretching out before.” On my daily wandering, I think endlessly about the characters dancing about in my head, as vividly as I sort out real-life dilemmas that need the same attention to pacing. Walking connects us to all that swirls about before pen hits paper or brush slides over canvas or spice gets sprinkled into the dish. Walking journeys us along the path inside and out. Books do too.

How do books come into our lives? The cross-reference, the subtle connection and seemingly synchronicity, all fascinate me. One article leads to a novel, while that story leads you to explore your own writing. In February I came across what I consider to be one of the best essays I’ve read in a long time, which explored the Gilded Age of yesterday “with a fascination with wealth accompanied by a fascination with destruction and disruption—by a belief in the benefits of burning it all down” (Gopnik) and compared many of the elements to today using the fiction of Henry James. “Though James never uses the term “plutocrat,” plutocratic America is what he was examining. To what extent were his plutocrats like ours? The Gilded Age plutocrats made their money in steel (Carnegie), oil (Rockefeller), mining (Frick), and railroads (Vanderbilt), but in the main their business models were not so different from those of their counterparts today. Musk makes most of his money in hard industrial goods, mainly cars and satellites, while losing money on the digital-media front—just as that other carmaker, Henry Ford, futilely poured money into his antisemitic newspaper, the Dearborn Independent. Bezos, meanwhile, made much of his money by finding new ways for consumers to shop for more goods more efficiently while forcing smaller retailers out of business, exactly like Wanamaker and Woolworth in their day.” But Gopnik also reveals the differences, “Where the plutocrats of the first Gilded Age built the New York we love, our own plutocratic class has scarcely built a monument or public building of beauty.” And here is where I really started listening to the argument Gopnik was building, when he “explored the allure of anarchy in what may be [Henry James] finest Gilded Age novel”, The Princess Casamassima. Needless to say, that novel rose to the top of my pile until I arrived at the foretold tragic ending. Gopnik continues to lace his essay with fiction and history as he searches for a way to understand our present era. “If the outcome of this new Gilded Age seems likely to be dark, it is perhaps because we have fallen into the trap that Europe fell into in 1914, the belief that by burning down flawed institutions we can somehow relight a charismatic glow. They didn’t, and we won’t. ” I fear he is correct.

Some books stay with us for a long time, moving from bedside to armchair, carrying words that illicit change or action, while others simply get returned to the library or give-away pile after one reading. The odd and circuitous routes which my reading takes intrigues me. Next up for me is Dickens’ David Copperfield. Why you ask? Let me remind you of the first line: “Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.” Amazing, yes? I saw that line recently, not sure where, referenced in a blog or social media post or perhaps in something more high-brow, regardless, all the markings and signposts have reminded me to take this novel off the shelf. I have made a decent dent in the Dickens canon but haven’t yet read this classic. As I hope to be the hero of my own life, I enter the tome with all the optimism when giving over to such a legendary storyteller.

I am careful when deep into writing fiction to stay clear of reading anything close to my own work. I like to run wild in my own imagination and not stray over to familiar tropes or conventions. Right now I am busy with a futuristic novel, with an array of brilliant and odd outcasts who just might uncover a way out of the mess our generation is currently creating. An optimism born from observation of the natural world is one defining element I glean from reading Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, a quality which I hope to never neglect in my writing. “There it was–her picture. yes, with all its greens and blues, its lines running up and across, its attempt at something…With a sudden intensity, as if she saw it clear for that second, she drew a line there, in the centre. It was done: it was finished. yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.”

You might also like Rebecca Solnit’s WANDERLUST…maybe you’ve read it. It is wonderful!Sent from my iPhone

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the recommendation!

LikeLike

I love words too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bloggers unite 🥳

LikeLike

I love words also! ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tools of our trade ☺️

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s right! ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Inspiring. Thank you! 📚

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for stopping by 😍

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Next Moves | Nine Cent Girl